Should you ask whether or how much to buy?

- By Nader Tavassoli

- •

- 04 Oct, 2021

- •

Across four studies, my former doctoral student Matteo Visentin and I demonstrate that people are more likely to buy (but not to buy more) when directly asked how much to buy in response to a set of quantity options than when first asked whether to buy in response to a seemingly innocuous yes/no purchase-interest question. For example, in a study using actual half-price lottery tickets, nearly twice as many participants (62%) bought one or more tickets when selecting among quantity options ranging from 0 to 5 than those participants (34%) who were first asked to respond “yes” or “no” to “Are you interested in receiving part of your payment in the form of Monopoly® instant scratch cards?”

We explain this finding in terms of how the response scales are partitioned. Our purchase-quantity scale has a single negative (0) and five (1-5) positive response options. In contrast, a dichotomous yes/no purchase-interest question has an equal proportion of negative (“no”) and positive (“yes”) response options, the latter of which subsumes all positive quantity options into one partition. While people did not appear to be randomly deciding whether to buy in response to either scale, the number of positive options anchored their decision to do so. In fact, the effect was eliminated when participants had their purchase interest assessed used a single negative (“no”) and five positive response options (“mildly,” “somewhat,” “likely,” “very,” and “definitely”).

Our findings are of interest to sales and marketing, including in the charity and health sector. They suggest more people will donate online when directly offered donation options (“No thanks”, $1, $5, $10, and “Other amount”) than when first required to make a yes/no decision to an initial “Donate Now” option. Similarly, a fitness app reminder that includes one “not now” and multiple positive options—such as “walk 500 steps,” “walk 1000 steps,” and “walk more than 1000 steps”—should lead to a higher incidence of people taking a walk than a dichotomous “let’s go/not now” response format.

You can access the research here https://rdcu.be/cyEGw.

On the eastern edge of the Himalayas, sandwiched between China and India, lies the small, land-locked Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan. Famous for its fortresses (dzongs) and fascinating cultural traditions, it offers some of the world’s best hiking, lush valleys, snow-capped mountains, and pristine lakes and rivers teeming with marine life. Paro Taktsang (Tiger’s Nest), which clings dramatically to cliffs above the Paro Valley, is one of many sacred monasteries. A mystical destination, Bhutan is also known as “the last Shangri La” – a path to self-discovery and enlightenment.

In terms of sustainability, Bhutan’s environment ranks high. Seventy-one percent of its territory is under forest cover – with a minimum of 60% being constitutionally mandated – and some 95% of its electricity is produced using hydropower, contributing to Bhutan being designated the world’s first carbon-negative country in 2017.

But how can a country ensure it remains this way? Bhutan’s recent re-pricing of its tourist tax and re-branding of its nation is an interesting case in hand, one that highlights the use of market-based interventions to address so-called “market failures” in the provision of public goods, such as the quality of the environment.

Gross National Happiness

For Bhutan, the greatest public good is happiness. In 1629, Bhutan’s ancient legal code had declared: “If the government cannot create happiness for its people, there is no purpose for the government to exist.” In 1972, the fourth king of Bhutan proclaimed: “Gross National Happiness (GNH) is more important than Gross Domestic Product (GDP).” Today, all government policies – including their tourism policy – are evaluated on their impact on a GNH index that includes measures of good governance, sustainable socio-economic development, cultural preservation, and environmental conservation.

“High Value, Low Volume” tourism

Bhutan first welcomed tourists in 1974, and for years brand Bhutan’s slogan was “Happiness is a Place”. By 2019, tourism was contributing to 6% of its GDP, and had evolved into one of the most important economic sectors, second only to hydropower. It is estimated that 16% of the working population is dependent on tourism.

Guided by a “High Value, Low Volume,” Bhutan has won several international awards for sustainable tourism. “High Value” relates to the targeting of mindful and responsible visitors, ensuring high revenue per visitor, and supporting a quality tourism infrastructure. “Low Volume” aims to ensure that the number of tourists is compatible with the carrying capacity of the natural environment and infrastructure. In short, Bhutan aims to avoid hyper-tourism and its damaging effect on the environment.

While tourism can provide significant economic benefits, over-tourism is ruining some of the world’s most perfect places. To combat this, many governments rely on tourist taxes that go towards maintaining tourism facilities and protecting natural resources. For example, the Italian city of Venice has an “overnight tax”, paid directly to the hotel on the first five nights of a stay (€3 a night for a three-star hotel, €5 a night for a five-star one), and is poised to introduce a €5 entrance fee for day trippers in 2024. In Thailand, international arrivals by air are charged US$8, while those arriving by land and sea pay $4. Most Caribbean countries charge a departure tax, such as the $18 by cruise ship, $20 by sea, and $29 by air in The Bahamas.

In Bhutan, tourist taxes have existed ever since it opened its doors to tourism in 1974. Back then, the tax was part of an all-inclusive fee of $130 per person per night. This fee also covered hotel costs, guides, local transport, food and non-alcoholic drinks.

In 1991, tourism was fully privatised along with a higher $250 daily fee for non-regional visitors – with a $50 discount from December to February and June to August when it was too cold or too cloudy to really profit from the Himalayan setting. This amount represented a bundle of fees. One was the daily $65 Sustainable Development Fee (SDF), or tourist tax, that went directly to the Bhutanese exchequer to fund cultural, environmental, and social projects. The remainder covered a three-star hotel – tourists had to pay more for higher-quality ones – food and non-alcoholic drinks, local transport, group guides, and entry fees to tourist attractions; thereby including most daily expenses for those on a tighter budget.

Only a few regional citizens had been exempt from this fee, such as those from neighbouring India who made up around 73% of visitors to Bhutan in 2019. This changed in 2020 when a $16 daily fee was imposed on regional visitors, most of whom represented budget travellers.

During the two years of the Covid pandemic, when it closed its borders, Bhutan took the opportunity to create a new brand and logo to re-define tourism and boost its nation’s image. When it reopened in September of 2022, it launched its new slogan “Bhutan Believe” – a rallying cry that encapsulated the nation’s values, global contribution, responsibilities and future. A visual identity drew on the vibrant yellow and orange of the Bhutanese flag, the emerald green of the forests, the blue of the national flower (the Himalayan blue poppy), and a soft black that referenced the natural soot in the country’s hearths.

“The new Bhutan brand is exciting – and so different from anything else,” said Carissa Nimah , chief marketing officer of Bhutan’s Department of Tourism at the time, “It is a huge honour and a pleasure to be part of this transformation, and to help facilitate tourism as a strategic driver of positive change and growth across the country.” 1

Re-pricing happiness

Most significantly, the rebrand came with a new tourist tax structure. Non-regional visitors would now pay a daily $200 SDF directly to the government (children aged five or younger were exempt and those aged 6-12 received a 50% discount). This tax was initially applied regardless of season or length of stay.

The rationale behind the SDF increase was that the old fee did not sufficiently detract budget travellers; and that local operators were observed to have skimped on quality to sustain on their allocation of the previous all-inclusive fee of which the former $65 SDF had been part of. Dorji Dhradhul, Director General of Bhutan's Department of Tourism, commented: “We are targeting mindful travellers who are sensitive to our culture, environment and aspirations. Although our policy is ‘High Value, Low Volume’, that was getting derailed. The pandemic gave us the opportunity to bring our tourism back on track.”

With the stand-alone $200 daily SDF, tourists now had to pay for everything else out of pocket – essentially, unbundling local costs and providing greater flexibility in choice. Non-regional visitors were required to stay in a tourist-standard hotel certified by the Department of Tourism, with prices for a qualifying double room in the capital Thimphu during peak season ranging from $50-$90 a night to more than $2,000 for a luxury establishment.

Self-catering visitors stood to pay $10-$15 for basic meals at one of Bhutan’s 4,200 restaurants and cafes, and $10-$25 in entrance fees to museums and local attractions that were once included in the daily fee. Optional extras might include spa treatments, kayaking or mountain biking ($35 a day) and white-water rafting ($250 for up to six per trip). Visitors arranging their own travel also had to hire mandatory private guides (around $20 a day plus tip) and drivers when travelling outside of the city ($15 a day plus tip). Bhutan had cemented its place as one the most expensive tourist destinations on Earth!

A blow to (some in) the tourist industry

Most agreed that the tourist tax had been due for a review when taking inflation and GDP growth in visitor countries since 1991 into account. However, the steep increase in the SDF for non-regional tourists and the $16 fee for regional ones came as an untimely blow to some in the Covid-battered industry. Many blamed the new tax on the fact that only 89,326 tourists had visited Bhutan from the country’s re-opening on September 23, 2022, to October 1, 2023, far fewer than the 315,599 in 2019.

Government officials counter-argued that the fee was part of a wider upgrade to the tourist experience. An improvement drive had been put into full swing during the pandemic. Upgrades included new restrooms, such as along the 250-mile Trans Bhutan Trail, face-lifts to tourist sites, and improvements to the online visa system and digital payments.

The Department of Tourism now also assessed hotels, guides and tour operators using more stringent criteria. This included a new “Competency Based Framework for Tourism Officer” backed by foreign-language, culture and history courses. These efforts aimed to promote Bhutan’s image as an exclusive high-end tourism destination, one that was aligned with the higher tax. However, the policy had its drawbacks. For example, licensed guide numbers dropped from 5,600 to 3,000; 30% of them did not pass the new assessment requirements, while others chose not to renew their licence. Further bearing the brunt of the changes were 650 one to two-star budget hotels that were initially no longer allowed to cater to even regional visitors from Bangladesh and India unless they could upgrade to higher standards. Only about 300 hotels had achieved this standard, with the “elitist” regulations viewed as favouring high-end hotels and resorts.

What followed was a sense of frustration about what exactly the re-pricing of the tourist tax and new regulations would achieve. The SDF fee was added to Bhutan’s general fund to invest in programs that would sustain culture, protect the environment, and upgrade the infrastructure. Yet it remained unclear whether the changes would benefit Brand Bhutan and support the government’s objectives and the nation’s happiness, or undermine these in the long term. Some suggested that Bhutan should pursue a different pricing strategy for sustainable development, although there was little consensus on what this might look like.

Duty-free gold and other initiatives

Indeed, regulators had quickly started tinkering with their market-based sustainability efforts. Most significantly, in September 2023, they reduced the SDF by 50% to $100 a day until at least 2027. They also introduced a tiered pricing system, whereby travellers could stay for up to eight nights when paying for four; 14 nights when paying for seven; and an entire month when paying for 12 nights. The government was also working with Drukair Corporation and Bhutan Airlines to reduce airfares, long perceived as too high by non-regional visitors. In one of the more creative approaches, Bhutan even started offering duty-free gold to visitors, as long as they spent at least one night in a certified hotel and paid for the gold in US dollars.

Tinkering with the tax structure to get it right came with its own problems, however, as tourists and tourism operators viewed the country’s policies as unpredictable. Designing market-based approaches to sustainability certainly looked to be a complex and uncertain undertaking.

Leveraging HR

According to The CMO Survey®, over two-thirds of marketing leaders have primary responsibility for the firm’s brand, but cooperation with human resources (HR) is significantly lower than with functions such as IT, operations and sales. This is a major shortcoming, as HR should have a leading role in taking people along the brand-internalization process – from understanding the brand promise to being motivated, enabled and rewarded for delivering the brand promise to customers.

Executing a differentiated brand strategy from the inside out necessarily involves familiarising employees with ‘Purpose, Vision, Values’ documents that clearly and precisely describe the brand, but rarely do. While many companies will share similar values (some version of customer centricity, integrity, sustainability, innovation, quality and teamwork), documenting the more unusual values and behaviours necessary to execute the unique aspects of one’s strategy – take Volvo’s “Safety First” or Tesla’s “Make It (Ridiculously) Fun” – is crucial if internal stakeholders are to join you on the journey.

Once a brand identity is agreed, it is then essential that HR leaders communicate it across all the 'moments-that-matter' in the employee journey. Differentiated recruiting ads will help attract on-brand applicants through self-selection, while the selection process itself should assess candidates in terms of brand and not just skill fit. The induction process offers a key opportunity to showcase the brand, one that immediately models on-brand behaviours and viscerally engages people for on-brand behaviours that are subsequently showcased and rewarded.

Crucially, while these activities appear most relevant for employees in customer-facing roles, they should be extended to all functions. For example, being a travel afficionado, whether in a client facing role, marketing, product development or even finance, complements Louis Vuitton’s travel-anchored brand DNA and requisite strategic investments. This holds across industries, whether it is McKinsey looking for a particular attitudinal and cultural fit or Red Bull seeking people across functions who are active in the cultural and sports domains they sponsor.

For companies that represent a house of brands, the undertaking will be more complex but not impossible to navigate. Work environments differ according to brands. The culture at Unilever’s Axe will be recognizably different from that of its Dove and Ben & Jerry’s brands. In these instances, group values should focus on shared drivers of success, while allowing sub-brands to adopt differentiating values, such as “history, generosity, savoir-faire, success, boldness and elegance” at LVMH’s Moët & Chandon, which are differentiated from its sister company Kenzo’s “love of nature, openness, youthfulness, joy and optimism.” Likewise, the contents of many other HR processes such as training or annual reviews should be differentiated across internal group brands as much as from those of the competition.

Segment internal audiences

Strong leaders will know that a one-size-fits-all approach will not work when trying to win over a large and diversified workforce. People need to be segmented both in terms of their functional roles: what it means to deliver the brand will be different for someone in finance (who needs to evaluate brand investments), product development (whose creativity should be stimulated by the brand), or sales (who needs to balance brand storytelling with closing the deal).

Recruit brand champions and leaders

People will also have different starting points when it comes to their brand engagement journey.

Developing and empowering a small group of opinion leaders across teams and departments as internal brand champions is critical to brand success. These individuals tend to be vital in winning over brand agnostics and converting antagonists who may have other ideas for what success looks like.

To maintain momentum, internal brand traction across these audiences must be monitored. This should involve employee polls that employ on-brand progress indicators, rather than only generic-by-design ones such as the Gallup 12. And, reflecting their strategic role, HR managers – if not the CEO – should be evaluated against brand-traction metrics, just like the Chief Marketing Officer is with respect to external brand health.

Of course, leaders at all levels need to model the brand through their own actions. It starts at the top. After all, many of today’s top brands are modelled on their founders, from Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel modelling female empowerment to Dietrich Mateschitz’s thrill-seeking lifestyle that continues to define Red Bull. Ideally, each next generation of leaders is not only attracted by and selected based on the brand DNA, but is also creative and authentic at behaving on-brand when facing internal and external audiences.

Reaping the rewards

In 1955 in 'The Practice of Management', Peter Drucker wrote the “hardest thing for any big organisation is to keep execution discipline at the forefront.” Brands are a powerful organizational development tool to do so, by helping embed your strategy into the minds, hearts and hands of your people. Your role as a leader is to guide your people’s thousands of daily actions to align around the brand, making for a difficult-to-imitate competitive advantage.

Living the brand from the inside out not only pays with customers, but it also provides tangible savings that boost the bottom line. Hiring the right people produces productivity gains in two ways: externally, it improves the cross-functional delivery of a differentiated experience across customer touchpoints, from social media to purchase and service. Internally, gaining brand traction results in higher pride, a greater sense of common purpose, and higher motivation levels. And it should be no surprise that people like to work at organizations that provide an attitudinal and cultural fit, which reduces costly turnover.

(From: https://www.forbes.com/sites/lbsbusinessstrategyreview/2024/01/19/leading-brands-from-the-inside-out /)

A human resources (HR) director of a famous luxury brand once bragged to me, “Not only do customers pay more for our products, but we also pay less for talent!” While this may well be true, is paying lower wages based on brand power is really such a good idea?

A school of thought known as “efficiency wages” challenges the seemingly straightforward notion that paying less results in higher profits. In reality, higher pay can lead to greater profits because employees work harder and stay longer – with productivity gains and employee turnover savings outweighing the increase in compensation costs.

My recent paper in Journal of Marketing Research (co-authored with Christine Moorman and Alina Sorescu) looked across industries shows that how a brand is viewed adds a surprising twist to the story. Specifically, we find that only brands perceived as “better” in terms of brand quality tend to pay less – resulting in a false economy consistent with efficiency wages – whereas brands perceived as “different” in terms of brand uniqueness pay more, but unknowingly boosting the firm’s bottom line.

Why do brand perceptions of being “better” or “different” affect pay?

Brands vary along two fundamental dimensions: the degree to which they are perceived as better (what academics refer to as vertical differentiation) and different (horizontal differentiation). For example, Lexus is seen as high quality, but not particularly unique. In contrast, Jeep is viewed as unreliable and therefore lower in quality, but it is uniquely perceived as rugged. Of course, brands can be perceived as low or high on both dimensions. Take, for example, Dior and Gucci: They are both universally valued for the quality of their craftsmanship and heritage of excellence. They are also different, with Dior renowned for its classic femininity and Gucci for its fashion-forward androgyny. Consumer preferences come down to a matter of taste.

So why would high-quality brands extend job offers with lower pay, and why would employees accept them? The answer is that well-regarded brands receive a greater number of qualified applicants, who count on the fact that being employed by them provides résumé power. The brands’ perceived quality literally rubs off on the employee and, knowing this, employees are willing to substitute lower current pay for more lucrative future job opportunities elsewhere. These dynamics provide high-quality brands with significant bargaining power – something many of them leverage to attract talent for less.

Brand uniqueness doesn’t offer the same advantage, because HR is tasked with finding a particular type of employee whose idiosyncratic characteristics help build and deliver the brand – be it in a customer-facing position or behind the scenes. For example, Dior’ s femininity, Gucci’s androgyny or Wildfang’s “tomboy chic” are each best suited by a different type of employee. Similarly, being a travel afficionado – whether in a client facing role, marketing, product development, or even finance – complements Louis Vuitton’s travel-anchored brand DNA and requisite strategic investments. These dynamics are found across industries, whether it is McKinsey looking for a particular attitudinal and cultural fit, Pampers selecting people who are passionate about infant care, or Red Bull favouring people active in the cultural and sports domains they sponsor. The nub is that HR needs to work harder to identify and attract matching talent when brand uniqueness is at play. And, when they find a match, they will not skimp on pay, especially as these candidates know their brand fit offers extra value.

HR is myopic about the consequences of these brand-based pay dynamics

Importantly, our research reveals that these pay decisions affect profits in unexpected ways. Specifically, we find that employees who might have been glad to accept less pay at high-quality brands end up putting in less extra effort and exhibit higher voluntary turnover – no doubt, in part, because they now have a stronger résumé. We find that these negative employee behaviours cost brands more than they save by offering lower pay, resulting in lower profits.

In contrast, firms that offer higher pay to employees who match their brand’s uniqueness tend to see this higher pay more than made up for in productivity and retention gains. The higher pay motivates employees to go the extra mile and their better fit creates complementary value. Association themselves with a unique brand will also not provide employees universally-valued résumé power at other firms, meaning employees are less likely to achieve the same higher pay elsewhere. Employees therefore tend to stick around longer, thereby saving brands hiring and on-boarding costs.

Unfortunately, unlike compensation, these productivity and retention dynamics and their financial consequences are difficult to observe, which leads firms to make suboptimal pay decisions with respect to both brand dimensions.

A call for marketing, HR and finance to better align their efforts

The bottom line is that HR managers at high-quality brands should use this brand power to attract talent, but not to supress pay, as doing so will ultimately hurt profits due to lower productivity and higher employee churn. Conversely, brands should seek out and be willing to pay more for talent that matches their brand’s uniqueness, trusting that this will eventually pay off in terms of productivity and retention gains. These brands benefit from hiring people who possess an excellent cultural fit and who authentically and naturally bring the unique brand differentiation to life.

This is easier said than done, of course, and there are structural impediments to getting it right. Specifically, The CMO Survey ( www.cmosurvery.org ), of which I am the UK Director, finds that marketing’s cross-functional cooperation with HR and finance is significantly lower than with IT, operations, and sales. In fact, marketing’s cooperation with HR and finance is the lowest overall. We hope that our research will encourage marketing and HR, in particular, to bridge this gap and work together closely to build and leverage the brand in attracting, rewarding, developing, and retaining the “right” talent.

Citation : “Brands in the Labor Market: How Vertical and Horizontal Brand Differentiation Impact Pay and Profits Through Employee-Brand Matching,” by Christine Moorman, Alina Sorescu, and Nader T. Tavassoli, Journal of Marketing Research , 2023.

Cheaper, faster and stronger are the value drivers that business has prioritised for more than a century. We call them efficiency and effectiveness. The importance of experience, the third ‘E’ in this equation, is also undisputed, but its sheer magnitude is not. As Peter Drucker summed it up neatly when he said: “The customer rarely buys what the company thinks it is selling.”

In today’s global marketplace it’s time to review the accepted hierarchy of the ‘3Es’. I’m going to put the case for experience to leapfrog to first place. Why? One reason is that it’s difficult nowadays to create or sustain an advantage based on efficiency or effectiveness. In terms of efficiency, your prices need to be competitive to be considered, but with few exceptions it’s not the reason you’re chosen over your closest competitors.

Ditto for effectiveness. Your products and services need

to be of the requisite quality to be considered, but any value difference is

ever more quickly imitated. Businesses are running faster just to stand still

when it comes to efficiency and effectiveness.

I also believe it’s time to reconsider just whose

experience we’re looking at: it’s fashionable now to talk about customer

experience – and that’s valid – but businesses could truly differentiate

themselves by looking beyond the purchaser to the user – the consumer.

Efficiency still counts

This isn’t to say that you don’t need all three of the

‘Es’ to be successful – on the contrary. Cost-cutting is often essential. PWC’s

survey of global CEOs last year found that 70% were launching a major

cost-cutting initiative, roughly the same percentage as in the previous two

years.

But common sense – supported convincingly by Deloitte

data across industries – suggests that businesses simply cannot create maximum

value via cost-cutting alone: companies tend to be value-creating (profitable)

when they have higher-than-average costs compared to their peers and

value-destroying (unprofitable) when their costs are below average. So, when it

comes to efficiency, the hard-to-achieve

objective is to identify and cut the bad costs (the fat) and avoid cutting the

good costs (the meat) that are investments in increasing effectiveness.

Effectiveness matters

The challenge of competing on effectiveness, on the other

hand, is twofold. First, in a global world, competitors will quickly follow

suit when a quality advance has market appeal. Second, as industries mature,

effectiveness gains rapidly hit diminishing returns, until customers no longer

care about any performance difference between close competitors. Consider

Gillette, which launched the disposable safety blade in 1903. It lasted most of

a century, until the dual-blade Sensor Excel in 1993. Then, just five years

(but more than US$1 billion in research, development and marketing) later, the

Mach3 added a third blade. Rival Schick hit back with a fourth blade in 2003,

so Gillette launched five blades in 2005. And 2016 brought a six-blade trimmer

from Korea’s Dorco. But don’t hold your breath for a Gillette Mach7 any time

soon. Like most maturing industries, each successive blade delivered nowhere

near the incremental value of the previous one.

Greater expectations

However, companies continue to conduct competitive

benchmarking studies in which they visualise the customer value proposition

using effectiveness curves that measure the performance of certain attributes

against the competition. An airline might consider its perceived on-time

arrival performance and use this to decide whether a price premium is justified

should they out-perform the competition (a point of difference), or a discount

if they lag (a point of inferiority). Unfortunately, based on competitive

benchmarking and diminishing returns, customers subjectively perceive most of

these dimensions as points of parity. They award little credit to a safer

airline because they wouldn’t consider flying with an unsafe airline in the

first place. It’s important for the customer, but not in their choice of brand.

In B2B procurement, suppliers have to meet standardised performance levels,

creating commodity-market conditions that put tremendous pressure on prices.

But the real problem inherent in effectiveness thinking

might be best illustrated by Michael Porter’s value chain, a concept core to

companies’ operating models. The ever-popular value chain visualises a chain of

activities common to all businesses, horizontally displaying primary activities

– operations, service, logistics, marketing and sales – and vertically

displaying support activities, such as procurement, HR, technology and

infrastructure.

This effectiveness model presents a fundamental challenge

to the efficiency thinking that guided the design of the assembly line in

manufacturing. Whereas efficiency is all about producing the same level of

output with less input, effectiveness is about producing a higher level of

output with the same level of input. Both of them lead to productivity gains,

but they have a radically different philosophy.

Mapping and measuring the customer journey, or its close relative the sales funnel, is a model that has survived for over a century. With big data providing insight into what customers searched and bought with incredible precision, it remains a powerful tool in helping companies capture value for themselves. But to capture value, companies must actually create value. And what a sale creates for the customer is a cost.

Value is created by the consumer, who might be a different person from the customer altogether: a parent who shops for the child or procurement in business-to-business settings who purchase but do not consume the offering supplied. Many businesses are still in their infancy when it comes to competing strategically on the basis of the consumer experience.

Do you put enough effort into making sure the consumer gets as much out of what they paid for as possible? My guess is not.

Fortunately, we are on the cusp of change. We are at the dawn of the age of the consumer, one fueled by a new type of big data around how consumers are actually behaving – whether it’s fitness bands that track how fast and far you run to the industrial Internet that has transformed how Volvo trucks serves its customers. The old maxim says, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. Well, when it comes to the consumer journey, increasingly you now can.

Those companies that are focused on the consumer journey, with its many moments that matter, are having a transformational impact. They are not just providing the basis for value creation, they are making sure it’s maximally achieved. As such, the consumer journey, of which the customer journey is only a small and discrete part, will be the real spine of competitive differentiation going forward.

Gift cards should be a triple-win: a happy retailer with cash in the bank, a relieved giver spared time, and a grateful recipient with welcome choice. Unfortunately, a solid one-in-ten of them present a triple-loss, though retailers seem blissfully unaware of this.

The UK’s first gift voucher, a humble book token, was first issued in 1932. According to the UK Gift Card and Voucher Association, the UK’s voucher and gift card industry has since grown into a £5.6 billion monster that consumes nearly £600 million in what appear like costless profits– either from customers missing the expiration deadline, losing them or simply forgetting about them. With those sorts of figures, isn’t the bad PR around consumer protection worth putting up with?

The simple answer is no, it’s not. It’s not only about the poor consumer experience. It’s also bad for brands, who cannot know how many customers and givers resolve never to return or recommend. Gift cards are bad for long-term profits, too.

Businesses may be forced to extend or even remove expiry dates on gift cards (the UK government has already urged self-regulation) – but they should not wait for this. They should act now out of sheer self-interest.

Here’s why. Wasted gift cards are not extra profits. The short-term profits that are so visible are more than offset by the loss of long-term profits that remain hidden. Set them against brand damage or loss of the far greater gains that come from redeemed vouchers and they are what economists call a false economy. As a marketer, I prefer ‘false profits’.

Businesses should remove expiry dates entirely – not just extend them. Indeed, they should actively encourage redemption. Recipients are customers as much as purchasers in this case – possibly new customers that a brand has not had to do a thing to acquire.

Instead of waiting for regulators to rectify the situation – as they did with bank overdraft charges and mobile phone roaming fees – it’s time for brands to save themselves from their own follies.

Five reasons to act now

- Consumers with a gift card spend on average 40% more in store or online than its face value – that’s a win worth chasing

- Gift cards and vouchers introduce new customers. A referred customer can spend up to twice that of a regular customer over their lifetime

- Gift card-referred customers are themselves up to twice as likely to refer than regular customers are

- A bad experience can turn both recipients and embarrassed givers into brand detractors who gripe to family, friends, colleagues and even journalists, regulators and legislators. Social media makes this very easy and effective. This is a terrible ‘two for the price of one’

- Handling expired vouchers and gift cards can drive up service costs and demoralise frontline employees with the disgruntled customers’ complaints and demands.

Star treatment – Michelin style?

Here is a case study of the impact of poor gift-card practice. It involves a certain Michelin Star restaurant and me. After two unsuccessful attempts to book a table within the one-year redemption period, I was told that the £250 voucher was no longer valid only two weeks after its expiration. We are talking over 100 Starbucks raspberry and coconut cakes, at least at today’s prices.

The restaurant eventually relented – so remains nameless – but only after gentle prodding including a threat of complaining to the Michelin Guide had gone all the way to the chef. Apparently, he had no knowledge of this practice, one he was horrified to learn about. It was certainly at odds with the great lengths his team went to delight and surprise customers in a positive way.

The chef admitted he would never cut costs on food, ambiance, or staff training. These are central to his business after all. Unfortunately, non-central practices such as gift cards that potentially upset 10% of customers remain under the radar.

Why the hated expiry date?

Some brands already issue cards with no expiry – such as IKEA, iTunes, Selfridges and Starbucks. Some have fairly long periods – such as Amazon (10 years) Marks & Spencer and The Body Shop (two years) or Argos and Zara (three years). Others, such as Costa Coffee, Ticketmaster, Habitat, Ted Baker and the above-mentioned Michelin star restaurant have just one year.

From a regulatory viewpoint, this situation is unfair. The customer bears the entire risk. The company has the money upfront – and can even make a tidy sum on financing the float – and there is no protection for theft, inflation or even the company’s insolvency. But what especially irks regulators is the expiration period. And, in recent months, the UK government has proposed all cards should have a minimum two-year expiry. Lord Foster, a Liberal Democrat business spokesman, wants the government to scrap use-by dates altogether.

The brands who issue them claim that each card must be logged and tracked on computer systems and that this causes administrative expense. And that allowing gift cards to sit on their books would create an unlimited liability, one that could cause problems if there were a run of redemptions. These arguments in favour of expiry dates are incredibly weak. And prioritising accounting neatness over fairness to ones customers certainly doesn't say much for the ethics of a business. If anything, the holders should receive preferential creditor status because the business has enjoyed their free money for no return. This, or some other underwriting pledge, would instil trust in the brand as well.

False profits

Producing false profits is a lot like strip mining your brand. They tend to produce short-term profits while eroding long-term gains.

Banks often operate in virtual silos due to the inability to have one view of the customer based on legacy systems and legal firewalls. In the case of overdraft charges, they would have cold, hard cash that suggested these were not only profitable, but significantly so. But what they did not see was the effect this had on their best customers, those who were too busy making money – that often sat idle in their savings account while the current account was overdrawn – to manage their finances. When these customers were slapped with what amounts to loan-shark level charges, they were far less likely to trust the bank with other profitable services. They were also more likely to make another bank their primary one.

Ditto with telcos. They would assess sky-high roaming charges – even though often due to rates set by their counterparts – resulting in a non-trivial pot of cash for themselves. What they did not observe, however, is the lost money. Customers would switch off their roaming and rely on free wifi at a local Starbucks (who sold them a coffee by the way) or get a local SIM card at the airport. None of the profit models I saw included this deleterious effect on customer behaviour. And this does not even include the anger-fuelled social media rants and contract non-renewals that come from inadvertent bills running into the hundreds of pounds.

Other false profits come in the form of promotions. A fashion brand hooked on seasonal discounting learned this the hard way. Volumes made up for margins during the discount period, making it look like a profitable idea. What they could not see was that some of these customers would have bought at full price at a later point. And the effect was most pronounced on those who bought at full price just before the discount, which included many of their best customers. They changed their behaviour by waiting for sales in the future or abandoning the brand altogether.

According to academic research and my own observations of these issues, these unknown unknowns are far more insidious than service failures or even public scandals, and no less harmful.

Some brands have even institutionalised false profits. I have learned of an airline that instituted a bonus system based on the over-weight baggage charges they manage to accumulate, as well as of a rental car company who offers gift vouchers to the rep having claimed the most damages on vehicles being returned (I wonder if these vouchers expire?).

But even if you are less aggressive about what surely are not long-term profit maximising practices, it is probably worth conducting a thorough analysis of your company profits, maybe guided by customer complaints. What is the percentage of profits that can be linked to customer complaints? Are these worth it? Common sense says no. But you can go further and observe the behaviour of customers hit with complaint-generating profits. If you have the CRM data there might be some indication. In order to get a real handle on them, you may need to run an experiment with a control condition, but in my experience, even a systematic look at customer-level data over time can serve as the business case for halting these practices.

As for voucher and gift cards, treating your customers this way is not just unethical, but plain old stupid. My advice is that if you offer them, eliminate the expiry date and make sure the card or voucher does not get lost or forgotten. After all, not serving a customer is no way of creating repeat business.

A version of this entry was published in the London Business School Review

Maybe the Brexiteers didn’t expect to win the referendum in June 2016. To quote from the confusingly-titled iconic Brit film, The Italian Job, maybe they “only meant to blow the bloody doors off”. Possibly they didn’t intend to shatter the whole edifice: they fled the scene so fast it’s hard to know. No matter. In uncertainty, as everybody knows, there is opportunity. And for Brand Britain to grasp this opportunity, it cannot afford the British habits of self-deprecation and ambivalence. Brands need to know what they’re about. And behave accordingly.

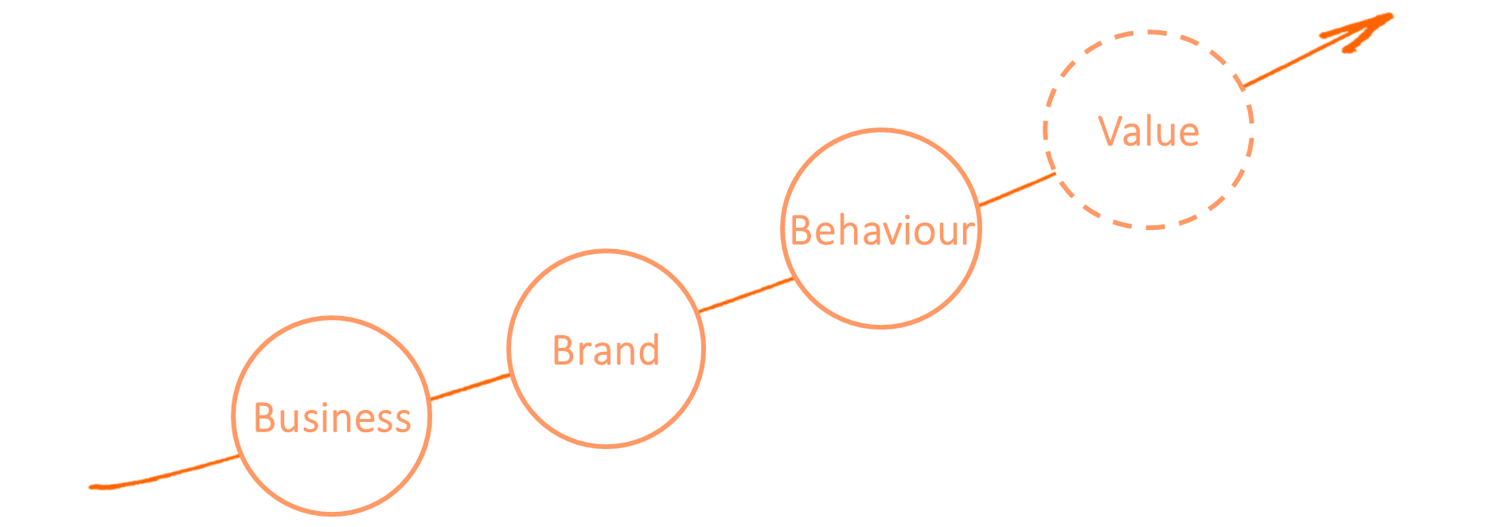

I don’t know how Britain will emerge from Brexit – who does – but I do know that it could help to look at it from a brand-building perspective. I have a 3Bs framework for this: aligning business, brand and behaviour. Maybe if Britain learns from corporate experience, it can avoid becoming a nation of Bregretters.

Seize the moment

With the world watching, attempts to shape Britain’s brand will have a disproportionate impact, amplified internationally by the press and social media. That opportunity won’t last for ever. The British government can help people reconnect with their identity, reframe the values that define the culture, and position Britain's role in Europe and the wider world for a new era. Political leaders should not get caught up in short-term posturing on the terms of Brexit – or its £60 billion price tag. This behaviour will reflect on Brand Britain. Rather than think of it as a cost, it should be seen as an investment. The European Union (EU) is not the only one listening and Brand Britain is a far greater prize at stake. Ultimately, brands are about identity and emotions. And, without empathy, Brexit may well have the same chilling effect of the separation of the British Isles from continental Europe following the last glacial period.

So let’s look at corporate brands for inspiration on how it could and should be done.

A branded house or a house of brands?

What is the national brand in question anyway? Brexit is an abbreviation for “British exit” where “British” refers to the people of the United Kingdom, which includes Great Britain – comprising England, Scotland and Wales – and Northern Ireland. As such, the UK is not a branded house like London Business School (LBS). Rather, it is a house of brands such as Unilever that owns power brands such as Dove, Axe (or Lynx), Lipton and Knorr, to name just a few. Unilever is also the world’s leading ice-cream maker, with brands such as Magnum, Carte D’Or, and Solero that are part of the Heartbrand, and Ben & Jerry’s that is not. Unilever’s Global Chief Marketing Officer, Keith Weed’s views on the repositioning of their brand can be usefully applied and can be heard in an interview I carried out with him here.

The brand architecture is complex, but purposeful. Brands such as Carte D’Or and Solero have a different functional positioning – sharing and refreshment, respectively – but are united under the Heartbrand’s umbrella positioning of “euphoric fun”. This aims to turn Carte D’Or’s sharing into a much more active “bonding” and Solero’s refreshment into an emotional “uplift”. Furthermore, Unilever’s corporate brand has the purpose of “adding vitality to life”, which for example, drives product development into lower-sugar ice creams.

Britishness too is a layered identity. Think of the UK as Unilever, Great Britain as the Heartbrand – with England as Magnum, Scotland as Carte D’Or, and Wales as Solero – and Northern Ireland as Ben & Jerry’s. And, of course, each comes in different flavours, just like London, the Lake District and Cumbria are all English yet different. Britishness is layered on much older identities of being English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh, which continue to resist a homogenised British identity. People differ in the degree to which they consider themselves as English versus British, for example, with some rejecting either aspect entirely. And it gets even more complicated when considering the EU: Remainers might add a dollop of Europeanness to their identity, which surely is a concept entirely foreign to the identity of most Brexiteers.

Business: British brand DNA

These complex concepts must be defined when it comes to establishing the ‘B’ for “business” in my 3B branding framework, whether for a company or a nation. William Hesketh Lever, founder of Lever Brothers, defined the purpose for Sunlight Soap in Victorian England in the 1890s: “to make cleanliness commonplace; to lessen work for women; to foster health and contribute to personal attractiveness, that life may be more enjoyable and rewarding for the people who use our products”. These ideas still guide Unilever’s business, brands and behaviours today.

But what is the identity-defining purpose of a nation? A nation is a body of people of a particular territory, united by common heritage, history, culture, or language. And to (re)define the British brand, one must deep dive into its DNA, values, culture, key moments in history and the iconic people that continued to shape it.

The British national identity finds its roots at least as far back as Magna Carta in1215, still an important symbol of liberty today. Britishness has political and moral foundations, such as tolerance, meritocracy and freedom of expression. It is an identity formally established with creation of the unified Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, when England and Scotland agreed “a hostile merger”. What was the purpose of this union? What led to its expansion to include Wales and Ireland later on? Or the demerger of the Republic of Ireland in 1922?

Purpose and identity are closely linked, and the notion of Britishness was strengthened during the Napoleonic wars, when it was one defined primarily by virtue of not being French or Catholic. A more pragmatic purpose was the growth and wealth creation of the British Empire, one that cemented the union. Money is also part of the Brexit equation, but the Remainers missed a vital ingredient by ignoring the role that identity played during the vote. And the government is in danger of playing a short game by focusing on the uncertain economics of Brexit without understanding the vital long-term implications of a strong British identity. The Brexiteers certainly knew how to play up historic identity battles with the Continent and the otherness of immigrants to fuel patriotism. Identity is a powerful card being played around the world, and the UK government ignore it at their own peril – not just with respect to the UK’s role in the world, but the union itself.

To redefine Brand Britain, it is worth looking at what accompanied the Empire’s planting of the Union Jack across the globe: tea, tubs, sanitation, obscure sports and churches, as well as a love-hate relationship to Britishness. In making its mark in the world, the UK has needed a range of soft skills: persuasiveness, diplomacy, creativity, ingenuity. These are skills that Brexit Britain should consider rediscovering and using to their maximum potential.

Mass immigration to the UK from the Commonwealth after the British Nationality Act 1948, and from all over the world since, has created an eclectic and vibrant expression and experience of cultural life exemplified in London. More than 250 languages are spoken in the capital, which has the largest non-white population of any European city. The UK’s membership in the European Economic Community in 1973 and European Union since 1993 has left indelible traces of Europeanness on the British identity.

Akin to how corporate brand identities are established, it’s instructive to look at who the British celebrate as the best examples of themselves. In November 2002, a BBC poll of more than a million people identified their greatest Britons of all time. Winston Churchill topped the chart, with engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel in second place and Princess Diana in third. The list included artists, writers, royalty, scientists, explorers, military giants and, of course, a Beatle.

As the list illustrates, Britain has long been a hotbed of innovation, with major contributions to global culture, literature and the arts. Brits contributed to world-changing inventions in global communications (electronic telegraph, telephone, worldwide web), the media (photography, television), industry (cement, stainless steel, spinning frame, steam engine, electric motor), and even the humble toothbrush. Its education system at all levels is envied and has been copied around the world. One should also explore what people think when they see a product is “Made in Britain” and how perceptions differ from the same product labelled as “Made in Germany” or as “Made in China”.

But a brand is not simply a laundry list of all possible ingredients that make up its DNA. As the British film producer and director Alfred Hitchcock has observed: “If you confuse the audience, they cannot emote.” And, in the end, this is an emotional and not just intellectual exercise. The genes of the DNA ingredients need to be boiled down and fit together as a coherent whole.

Brand: who is it for?

But to create a compelling brand, the DNA is not enough. One has to consider the voice of the target audiences, whose attitudes and behaviours the brand should ultimately affect. It is an exercise at small scale with the Red Arrows as part of our MBA programme’s London Business Experience immersion. The Red Arrows know who they are, but in order to be a force for stimulating UK economic growth – their new remit of their air shows when travelling the world – they need to understand the goals of their different audience members, and then marry these insights up with what their DNA has to offer. To do so, you have to look for a universal insight that unites, rather than differentiates these audiences. Unilever has many audiences ranging from their own employees to regulators, communities, investors, customers and consumers. But they all can relate to their corporate purpose.

The second ‘B’ for brand therefore marries the DNA with target stakeholder insights: from businesses, immigrants, tourists, students, governments, not to mention its own citizens. For whom, in the long-term, should the brand be crafted? What are their goals? In what ways can Britain and Britishness authentically relate to these? While the brand message can be articulated in different ways to different stakeholders, the brand idea must have a consistent and coherent voice. External stakeholders too have different goals: Brexit affects them in different ways. The remaining 27 EU members will certainly feel different about Brexit than non-EU countries, who see new opportunities in a more independent UK.

Starting internally may well be the way to go: finding common ground for a nation divided. London stands apart from most of England, and Northern Ireland and Scotland voted to remain. It is therefore important to not get seduced by the notion of trying to forge a new Britishness around the identity of the Brexiteers. Exit polls and regional voting patterns suggest that they were, on average, older and less educated than the Remainers. Also, as the polling organisation YouGov showed, the brands preferred by voters differed substantially, even when correcting for demographic factors. Those who voted to leave were most loyal to traditional and warm brands like HP Sauce, Sky News, PG Tips and Richmond Sausages; whereas those voting Remain favoured more progressive and innovative brands like the BBC, Spotify, Virgin Trains and Twitter. This is no value judgement but a call to look at what unites rather than what divides them.

Behaviour: what are the moments that matter?

Whatever brand idea is created at the overlap of the DNA and audience insight, this is only the design of the brand strategy – one that needs a plan to be successfully executed. This is where the third ‘B’ for behaviour comes in, and it presents probably the biggest challenge – for business or nation alike. This is not about the big campaign. This is about the thousands of behaviours that add up. Take Southwest airlines. They are not just cheap, but their brand promise to weary travellers is that it will be a cheerful experience. And their people exhibit true missionary zeal, with constant smiles and creative in-flight announcements. This is not the 4 Ps of marketing – product, price, place and promotion – but the Southwest’s 3 Ps of “people, personal and personalities” that are at the heart of its branding efforts. All of its people processes are dedicated to attracting, selecting, developing and rewarding the hardworking "Fun-LUVing Attitude" that is one of its core values. All this so that its people can deliver fun moments-that-matter.

And Southwest is an example not too far-fetched for Brand Britain to learn from. Think of all the touchpoints that a migrant, foreign student, tourist or business traveller has. From acquiring a visa (something millions more will likely have to do post-Brexit) to arriving at an airport such as Heathrow, there are thousands of experiences that will shape people’s perceptions of this nation. When Glasgow wanted to improve its image, city leaders worked with taxi drivers. These moments all matter. And there are usually humans behind them.

What’s crucial, of course, is that leaders themselves behave in line with the identity: this is where Britain needs to take stock quickly, or else lose this opportunity. Because your people are more likely to follow your example than your carefully-crafted words. Similarly, in Brexit Britain, though the Brexiteers insisted they did not want to keep out migrants who worked and paid tax, their message is interpreted bluntly by many who hear it. But building a strong brand is not just about avoiding missteps or misperceptions. It is about behaving positively in brand consistent ways, and the government is in desperate need of a brand playbook at this critical time.

Nader Tavassoli is Professor of Marketing at London Business School, where he founded the Walpole Luxury Management Programme, as well as non-executive chairman of The Brand Inside. This entry was published in the London Business School Review.